AI is deciphering a 2,000-year-old 'lost book' describing life after Alexander the Great

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, it carbonized a book on rulers who followed Alexander the Great. Now, machine learning is deciphering the "lost book."

A 2,000-year-old "lost book" discussing the dynasties that succeeded Alexander the Great may finally be deciphered nearly two millennia after the text was partially destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79 and, centuries later, handed off to Napoleon Bonaparte.

The reason for the breakthrough? Researchers are using machine learning, a branch of artificial intelligence, to discern the faint ink on the rolled-up papyrus scroll.

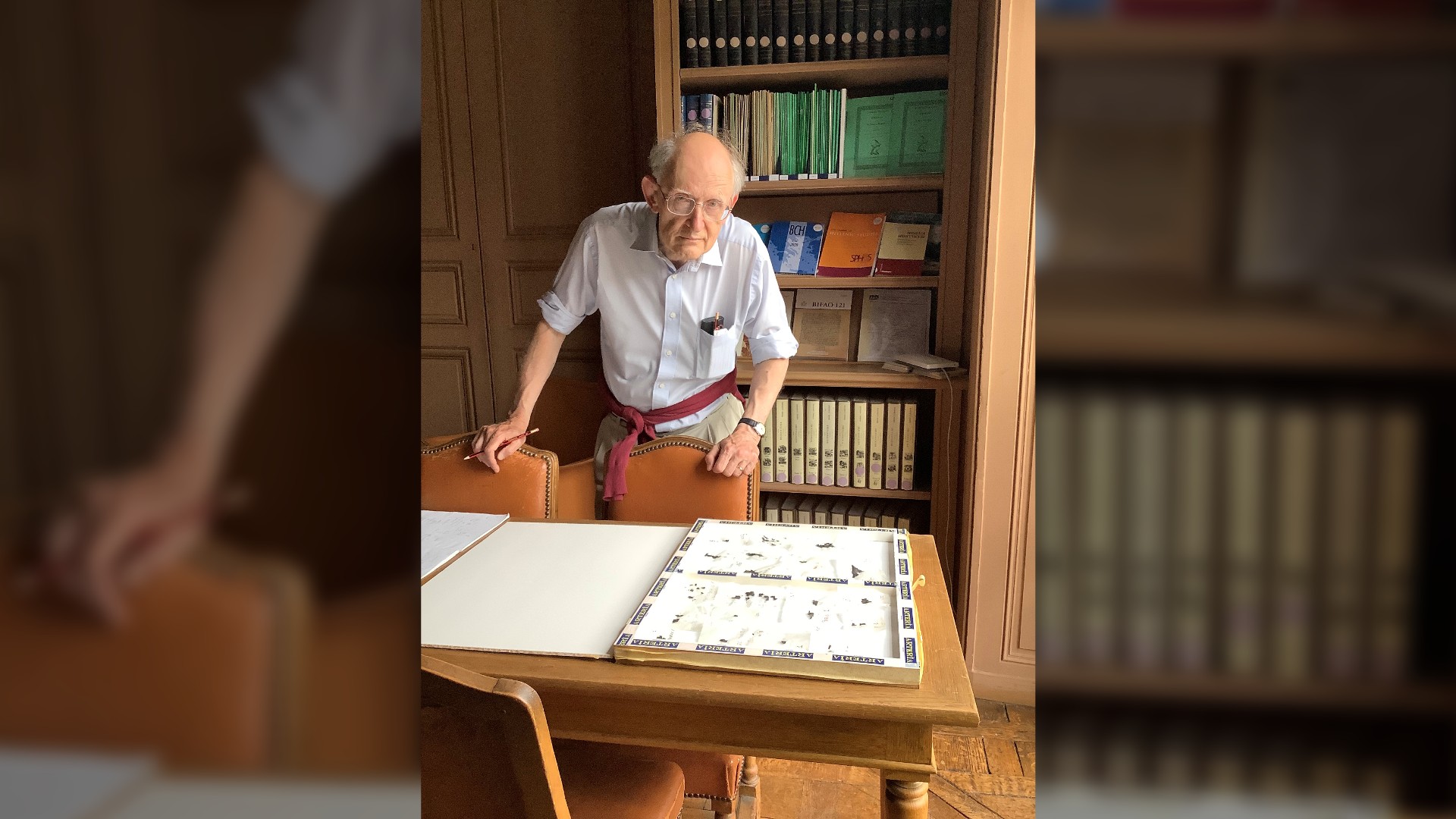

"It's probably a lost work," Richard Janko, the Gerald F. Else distinguished university professor of classical studies at the University of Michigan, said during a presentation at the joint annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies, held in New Orleans last month. The research is not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Only small parts of the heavily damaged text can be read right now. "It contains the names of a number of Macedonian dynasts and generals of Alexander," Janko said, noting that it also includes "several mentions of Alexander himself." After Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C., his empire fell apart. The text mentions the Macedonian generals Seleucus, who came to rule a large amount of territory in the Middle East, and Cassander, who ruled Greece after Alexander's death.

The lost book is from the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, a city that was destroyed alongside Pompeii when Mount Vesuvius erupted after the turn of the first millennium. The villa, named for its vast scrolls of papyri, contains numerous writings from the philosopher Philodemus (lived circa 110 B.C. to 30 B.C.). These papyri were carbonized when the volcano erupted. At some point, the text was found, and it was given to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1804. He gave it to the Institut de France in Paris, where it now resides. In 1986, an attempt to unroll the papyrus resulted in further damage, Janko said.

Related: Battle site of 'Great Revolt' recorded on Rosetta Stone unearthed in Egypt

Revealing the text

Janko has been studying the papyrus with help from a team led by Brent Seales, director of the Center for Visualization and Virtual Environments at the University of Kentucky.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To uncover the papyrus's secrets, Seales' team has been using machine learning: They've trained a computer program how to detect ink on papyri by letting it analyze ancient scrolls with computed tomography (CT) scans, which take thousands of X-rays to make 3D digital images. "They have visible writing, so we can match up the ink locations with the exact place to search for that ink in the micro-CT," Seales told Live Science in an email.

During the presentation, Janko noted that the team's work is gradually making more of the text legible. "With each iteration of his [Seales] work, the ability to read more of these fragments is getting better every time," Janko said.

Many mysteries

However, much about the scroll remains a mystery. The author of the text is unknown. It's also unclear why it was inside the villa. Janko noted that many of the texts in the villa were written by Philodemus and discuss philosophy, not history.

Janko hypothesized that the text may have been borrowed and not returned. One possibility is that Philodemus himself used it as a reference to write his work "On the Good King According to Homer," Jeffrey Fish, a classics professor at Baylor University in Texas, told Live Science in an email. In this work, Philodemus compares post-Alexander kings with those who reigned earlier, casting the post-Alexander kings in a negative light.

The patron of Philodemus was a man named Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, a Roman governor of Macedonia. "I think Philodemus is showing Piso that the example of Homer's good kings can help him as governor of Macedon surpass the decadent Hellenistic rulers who preceded him," Fish said.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.